By Anna McCurley

By Anna McCurley

Every Halloween, some of the most popular costumes come with more than funny hats, swords, or fake blood – they come with copyright implications. Halloween costumes often correspond to the summer’s biggest blockbuster movie, popular cartoon princesses, or what’s going on in politics. This year, the winner of the coveted “most popular costume” prize is Wonder Woman and the two previous years it went to Harley Quinn. Halloween costumes are an opportunity to show humor, political views, fandom, admiration, and creativity. Such expression often entails the use (or misappropriation) of copyright.

However, this post isn’t about the elaborate costumes that exude fandom. This post is about cheerleading uniforms and bananas.

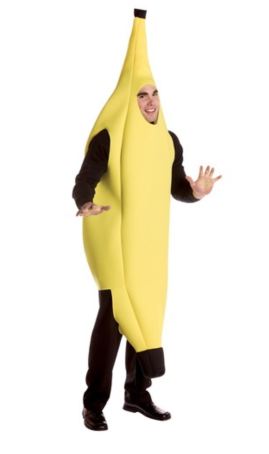

Rasta Imposta makes banana costumes. If you’ve shopped for Halloween costumes anytime in the past five years, you’ve likely seen one. Rasta has been producing banana costumes since 2001. In that time, they have sued four other companies for copyright infringement of their banana costume design. Three of those cases ended in closed settlements, most recently with Kmart Stores. One is still pending.

U.S. copyright law protects art, but not useful articles, and costumes occupy the murky space between the two. Things are even murkier in light of the Supreme Court’s newly-minted test for separating pictorial, graphic, or sculptural (“PGS”) works from associated useful articles under § 101 of the Copyright Act.

Decided in March of this year, Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands does away with the idea that the PGS elements of a costume must be physically removable from its useful aspects (serving as clothes) which the Second Circuit previously employed. The Supreme Court established a two part test: that a useful article (here, a cheerleading uniform) is eligible for copyright protection “only if the feature (1) can be perceived as a two- or three- dimensional work of art separate from the useful article and (2) would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work – either on its own or fixed in some other tangible medium of expression – if it were imagined separately from the useful article into which it is incorporated.” The court held that only the “two-dimensional work of art fixed in the tangible medium of the uniform fabric” was copyrightable. “[R]espondents have no right to prohibit any person from manufacturing a cheerleading uniform of identical shape, cut, and dimensions to the ones on which the decorations in this case appear.”

The Court focused its separability analysis on the admissibility of the PGS work after it is removed from the useful article. It did not require that, in so removing, a useful article remain behind. This allowance, however, does not allow for nothing to be left behind after separation. “[B]ecause the removed feature may not be a useful article … there necessarily would be some aspects of the original useful article ‘left behind’ if the feature were conceptually removed.” Importantly, the Court disposed of the notion that there was any difference between physically and conceptually separating the PGS work from the useful article.

Applying the Star Athletica test to the banana costumes currently at issue, one must first identify what exactly comprises the PGS element to be removed. Here, the banana costume itself is useful as clothing, but it is also the entire PGS work. For example, the lines down the sides of Rasta Imposta’s costume serve dual functions: as structural seams and as design elements. Removing the banana elements from the costume wouldn’t leave behind much, if anything at all. It doesn’t have to, though. Post Star Athletica, the focus is now on what the PGS work would be independent of the useful article, not on whether the leftovers are still useful.

Here, removing the PGS from the useful article might entail closing the openings which allow the costume to be worn: the arm holes, the face hole, and the gap at the bottom that rests around the wearer’s hips. Closing those gaps would remove the utility from the costume and turn it into a sculpture of sorts. The Court did say that some aspects of the original useful article would need to be “left behind,” but that requirement might not be literal. Here, eliminating a person’s ability to wear the costume serves the same function as “leaving behind” the utilitarian aspects that classified it as clothing in the first place. The question now is “how little can you leave behind?”

That the Supreme Court favors conceptual separation means that more artistic-utilitarian merged works may be protectable under copyright law. If physical separation was the standard, the banana costume would not be protectible because there would be no clothing left without the banana elements. This new standard will likely have meaningful implications for industries like fashion, expanding protection for works that at one point did not qualify.

However, Rasta’s copyright could still fall under the weight of a court challenge on other grounds. After all, bananas come from nature and there are only so many ways a person can wear a banana. If it fails, however, it likely won’t be under the Star Athletica test.