By: Alex Okun

As a general concept, Artificial Intelligence (“AI”) is not new: “chatbots” have been available for decades, and virtual assistants like Apple’s “Siri” first appeared 15 years ago. However, the latest iteration of AI – “Generative AI” – takes the concept one step further. Generative AI platforms can produce entirely new text or images based on prompts as short as a sentence. A new world of “AI art” has emerged online, and now many users are hoping to monetize their creations. However, consumers will not purchase a work from the creator if others can freely distribute copies of it. Effective commercial use requires the right to prevent third parties from doing the same, and to do that, one must first obtain a valid copyright.

Copyright Law’s “Authorship” and “Originality” Requirements

For a work to be copyrighted, it must be an “original work of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” A “work of authorship” requires an author, and the courts have consistently held that an “author” must be human. “Originality” requires that an author contribute “a modicum of creativity” to their work. However, courts have acknowledged that machines can be utilized to create a work without jeopardizing copyrightability. In the landmark case Burrow-Giles v. Sarony (1884), the Supreme Court held that a photograph could be “original” (and thus copyrightable) so long as it represents the photographer’s “intellectual conceptions.” While it is relatively clear when a camera manifests the user’s artistic choices, ambiguity arises when the machine also plays a role in creative decision-making. There is no question that AI-generated art is original; to be copyrightable, the question is where the originality came from.

Even if a work has sufficient originality, copyright will only protect the parts of it that manifest the author’s creativity. In Urantia Foundation v. Maaherra (1997), the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that “divine messages” in a book could not be copyrighted because they originated from a deity rather than from a human being. Similarly, the United States Copyright Office (“USCO”) in 2023 approved the copyright of an author’s comic book but denied protection to an AI-generated image depicted in it.

One route to copyrighting AI art is to include it in a compilation of works. A compilation can be copyrighted if the author selects or arranges works in a way that requires creative discretion (like selecting the “best poems of the year” or arranging art pieces thematically). The USCO acknowledges that compilations of AI art can have sufficient originality, but each work included cannot obtain a copyright absent sufficient human authorship. Thus, copyright authorities must determine how much creativity a user must contribute to an AI-generated image to be copyrightable.

On the docket

Several lawsuits have been brought against the USCO for denying copyright claims by users of Generative AI applications. In 2022, Dr. Stephen Thaler sued the USCO over its determination that he could not copyright an image produced by his Generative AI application, “Creativity Machine.” Thaler did not claim to be an “author”; instead, he listed Creativity Machine as his employee, who had created the piece at his direction. The District Court upheld the USCO’s decision in 2023, finding that the AI application could not be the “author” because it is not human. Thaler appealed the ruling in 2024 to the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, but hearings have not yet been scheduled.

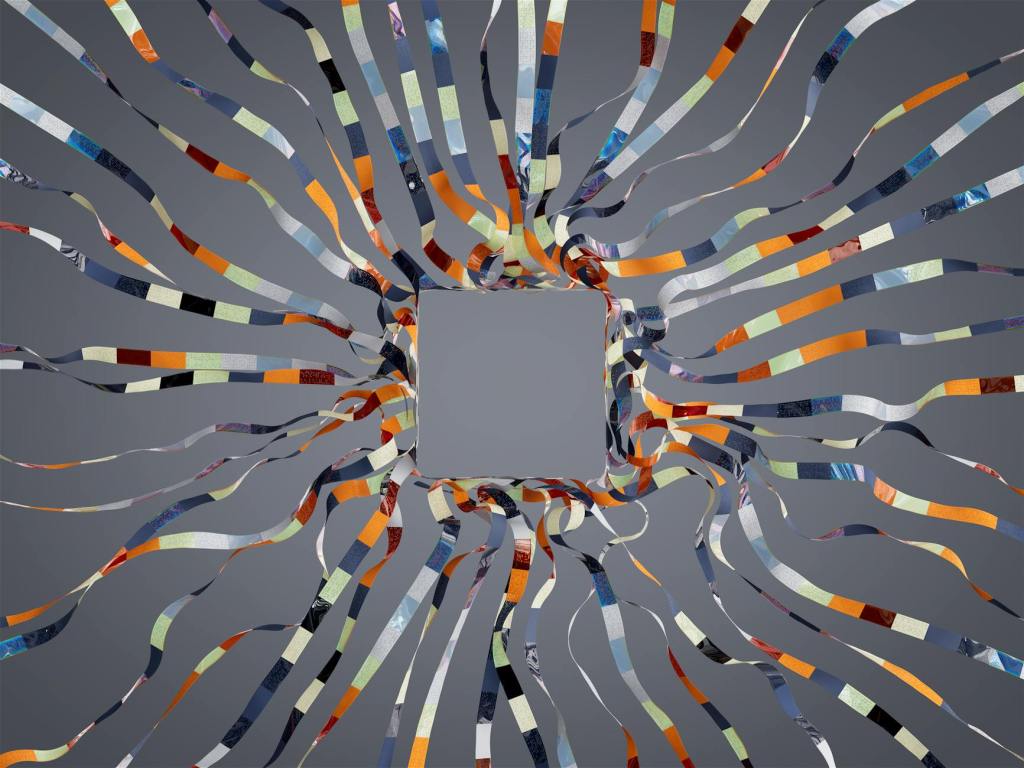

Whereas Thaler was focused primarily on the viability of non-human “authors,” a case filed in 2024 illustrates the legal issues arising from the “originality” requirement for AI users. In September 2024, Jason Allen sued the USCO for denying copyright protection for an award-winning image he created using the popular AI application Midjourney. He argues that the art was only partially generated using AI and that his contributions to the work justified a finding that it was sufficiently “original” to be copyrighted. According to filings, Allen inputted “at least 624 text prompts” to the application before the image created what he envisioned. Initial hearings took place in December 2024, but the court has not yet reached a decision.

Policy Changes

Distinguishing “machine-assisted” artistic works from “machine-generated” works has been a persistent issue for the USCO in the past several years. In 2023, the USCO issued ambiguous guidance that stated copyright protection in AI art depends “on the nature of human involvement in the creative process.” On January 29, 2025, the USCO issued clarifying guidance to resolve the confusion. It states unequivocally that “prompts alone do not provide sufficient human control to make users of an AI system the authors of the output.” To justify this policy, USCO pointed out that entering duplicate prompts multiple times can result in varying results. It also rejected the prospect of “revising prompts” (when a user enters subsequent requests to alter the initial image produced), likening it to “re-rolling the dice.”

The 2025 USCO guidance also distinguished mere prompts from “expressive inputs,” in which the user uploads media to the AI application and then asks it to modify the material in some specific way. Expressive inputs can merit greater protection because the user exercises greater control by giving the AI model a “starting point” rather than generating images from basic text. However, the USCO reaffirmed its view on severing the AI alterations from the author’s work and only protecting the user’s original work’s “perceptible” aspects in the new image. Of course, this categorically excludes AI-generated content based on media not created by the user.

In contrast, the United Kingdom’s (“UK”) copyright law specifically allows copyrighting “computer-generated” artwork and defines the author as the person who makes the “arrangements necessary” for its creation. This phrase leaves legal experts unsure whether this would mean the AI application’s programmers or its users would be deemed “authors” of AI art. However, the answer to this question may be of little consequence: many of the top Generative AI companies (including OpenAI, Midjourney, and Adobe) expressly grant their users full ownership of what they create. If US lawmakers chose to grant AI companies copyright protection in AI art, users might simply select the applications that promise to transfer ownership to them.

Conclusion

As US media companies increasingly rely on Generative AI, the ability to claim ownership in AI-generated work is a growing risk to business productivity. Resolving this issue is particularly important to content creators because production studios may need to continue relying on artists if they cannot copyright AI-generated content. Despite the greater specificity in the USCO’s new guidelines, the efficacy of these policies remains in question. The 2025 guidance is the second installment of a three-part report initiated in 2023, and it is unclear whether Congress or the Trump administration will attempt to modify these policies. Moreover, federal courts have the final say on these issues because the requirements of “authorship” and “originality” are constitutional questions. So long as this legal ambiguity persists, the “AI revolution” in the art industry will likely need to wait.