By: Claire Kenneally

CBP One: From Cattle to Children

CBP One, launched in October 2022, was a mobile app designed to expedite cargo inspections and entry into the United States for commercial truck drivers, aircraft operators, bus operators, and seaplane pilots transporting perishable goods. It allowed those entities to schedule an inspection with Customs and Border Patrol (CBP).

In 2023, the Biden administration expanded the app’s use to asylum seekers. CBP One was designated as the only acceptable way to apply for asylum at the border. To schedule an appointment, asylum seekers had to be in northern or central Mexico. After creating an account, they could request an appointment. Appointments were distributed at random the following day, a practice criticized for “creating a lottery system based on chance.”

Asylum is legal protection for individuals fleeing persecution based on their religion, race, political opinion, nationality, or participation in a social group. Asylum is recognized under international law and U.S. law. If granted, the asylee may live and work in the United States indefinitely. Asylum seekers apply either at a port of entry along the border, or after entering the U.S.

Texas National Guard on Rio Grande, Preventing Asylum Seekers from Entering by Lauren Villagram

The Human Cost of Faulty Technology

In researching this article, there were too many stories to count of CBP One’s dysfunction leaving migrants—already months into perilous and exhausting journeys—unable to claim their legal right to apply for asylum.

CBP One was plagued with regular glitches, errors, and crashes that would never be adequately resolved. The app regularly refused to accept required photo uploads, miscalibrated geolocations, and froze– causing the user to miss that day’s available appointments.

Many described the lack of appointments once they created accounts. Migrants in Matamoros were reported waiting up to six months in shelters, rented rooms, or on the street. Asylum seekers often travel by foot to the Mexican-American border and arrive with little more than the clothes on their backs. Most could not afford to pay for months in a hotel, and many experienced racism at the hands of Mexican nationals who refused to employ them. Waiting weeks, let alone months, was unsustainable. Read more about the wait times and the human impact here and here.

Other stories pointed out the inaccessibility of relying on a Smartphone app to secure an appointment with CBP. To use it “people need[ed] a compatible mobile device. . . a strong internet connection, resources to pay for data, electricity to charge their devices, tech literacy, and other conditions that place the most vulnerable migrants at a disadvantage.”

Those with older phones often could not comply with the required photo-upload, and were told to purchase a new phone if they wanted a shot at an appointment. This unexpected financial burden often proved impossible.

For those with limited technological literacy (the ability to use and understand technology), the 21-step registration system operated as a barrier to entry. Similarly, people with intellectual or physical disabilities were often unable to use the app.

A Place to Charge a Cell Phone [Was] a High Priority for Migrants Relying on Their Phone to Access the App by Alicia Fernández

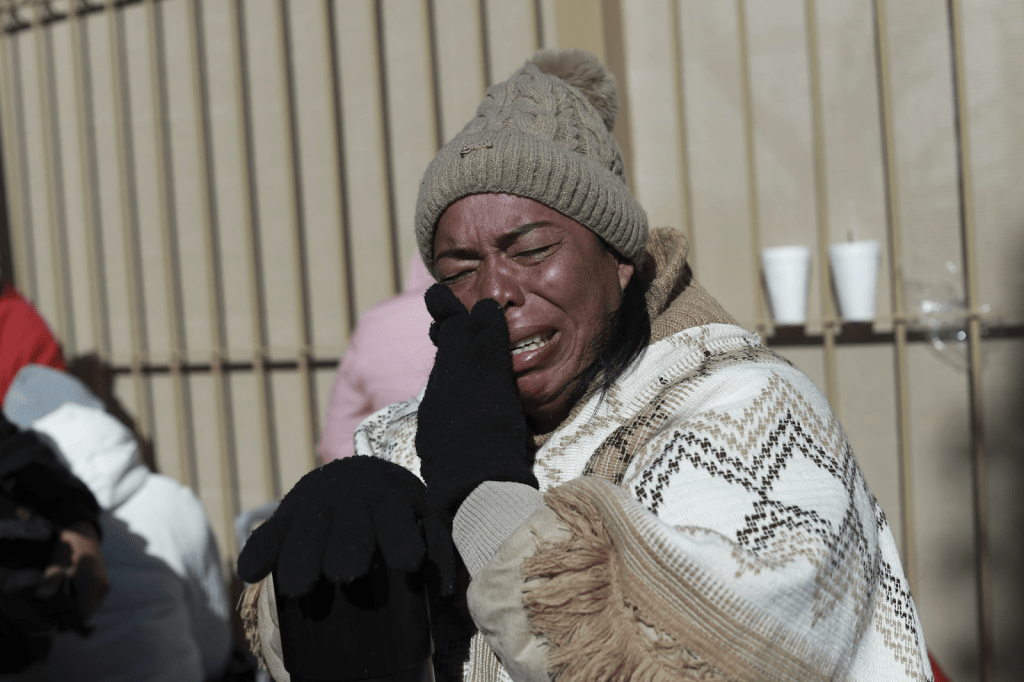

The app was only available in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole and plagued by racist facial-recognition software whereas it failed to register the faces of dark-skinned or Black applicants.

A Pressure Cooker at the Border

The CBP One bottleneck pushed Mexican border towns to their breaking points- resulting in exceedingly dangerous and unhealthy conditions for migrants waiting for appointments. Doctors Without Borders reported a 70% increase in cases of sexual violence against migrants in one border town last year.

Centro, a Mexican asylum seeker, waited at a shelter for nine months to receive an appointment. One of her three children has asthma and had to sleep on the floor. “He has been hospitalized three times because of the cold,” she says.

Shelters quickly filled to capacity. Migrants were then forced to sleep on the streets. There, they were subject to extortion, harassment, and assault at the hands of cartel members and military police. They routinely had no access to running water, electricity, hot food, or protection from the elements.

Mexican Migrants at the Juventud 2000 Shelter in Tijuana, Waiting for a CBP One Appointment by Aimee Melo

One Harmful App Replaced by Another

On his inauguration day in January 2025, Donald Trump cancelled that afternoon’s CPB appointments and ended asylum seeker’s use of the app. He also revoked the legal status (“parole”) of the 985,000 migrants who successfully entered the US after obtaining CBP One appointments.

Later that spring, the Trump administration’s rollout of a new app, CBP Home, offered no relief for the migrants at the border. Instead, the app greets asylum seekers currently in the U.S. by explaining the benefits of self-deportation.

Self-deportation through CBP Home alleges to provide immigrants with a free flight, a $1000 stipend, and the ability to reenter the United States “legally” in the future. To pay for these promises, the Trump administration moved funds earmarked for refugee resettlement to pay for the flights and stipends.

But the law does not recognize this self-deportation scheme. The Marshall Project notes that “migrants who leave through [Trump’s self-deportation] process may unwittingly trigger reentry barriers— a possibility that self-deportation posters and marketing materials do not mention.”

The $1000 stipend also has no legal backing, as there is no law authorizing payments to undocumented immigrants— meaning that there are no legal repercussions if the administration refuses to send the stipend to someone once they have left the country.

And where in this new app does an asylum seeker in Mexico book an appointment with CBP to request asylum? Nowhere. That process has simply been erased.

CBP One Data: Now Used to Fuel Deportations

When CBP One was active, asylum seekers were required to input a variety of information about themselves to create an account. There was no way to “opt out” of sharing the information the government demanded.

Now, using data obtained from those original profiles, DHS has begun stalking and harassing asylum seekers currently in the United States, urging them to “self-deport” with the new CBP Home app. This raises frightening ethical questions about data privacy, government surveillance, and how the information we provide can be weaponized against us.

Screenshot of the Department of Homeland Security’s webpage on CBP Home, taken by the author on November 12, 2025.

A Bleak New Reality

As of November 2025, the Trump administration has shut down asylum-seeking at the U.S.-Mexico border, trapped migrants in Mexico, and left those in the U.S. fearing their own data will be used to deport them. What began as a flawed app has escalated into something more sinister and predatory, and requires all of us to pay attention and to advocate for change.

#AsylumCrisis #DigitalBorders #WJLTA