By: Drew Carlson

What does it take to release a copyrighted work into the public domain? On September 15, 2023, writer Bill Willingham decided to test just that, releasing his comic book series Fables into the public domain after years of fighting with his publisher, DC Comics (“DC”). Can an author release a work into the public domain before the copyright protection expires? If the author is the legal owner of the copyright, then he or she may do so, but this is often not the case. Willingham will need to prove he is the sole owner of the Fables copyright.

Once Upon a Time

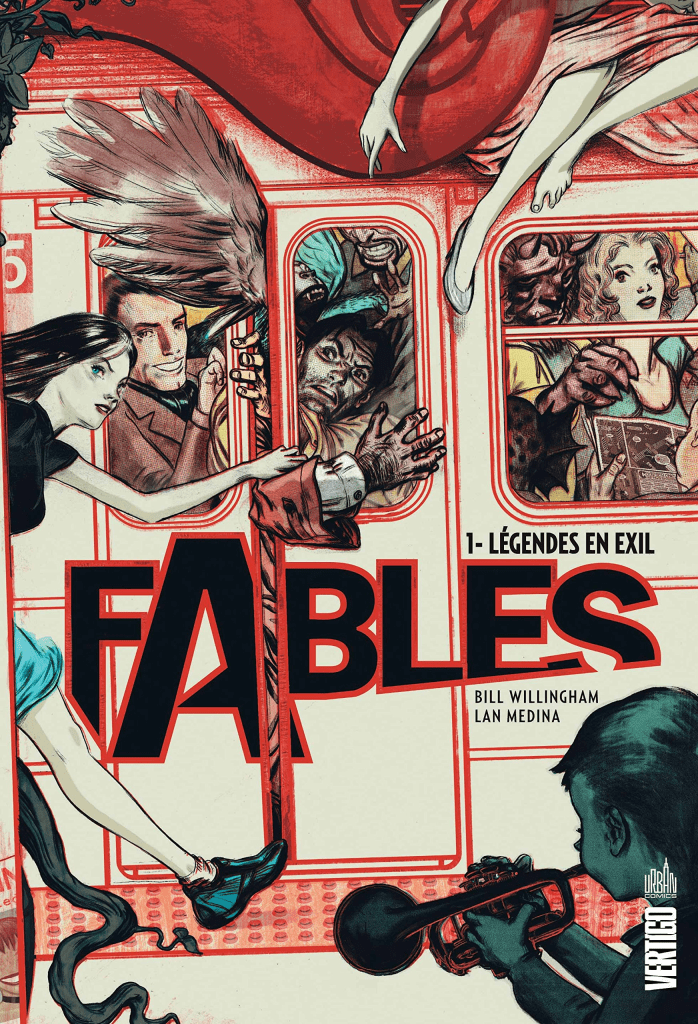

Willingham is the writer of the award winning comic book series Fables, published by DC Comics for their adult-oriented Vertigo imprint. The series is set in a universe where characters from fairy tales and folklore have taken refuge in modern day New York. They live in a secret community, hiding from both regular humans, and the Adversary who conquered their homelands.

According to Willingham, he signed a “creator-owned publishing contract” with DC, which made him the sole owner of the intellectual property but forbade him from “publish[ing] Fables comics” or licensing the property “through anyone but them.” The series’ copyrights were registered with the Copyright Office, each within two years of the work’s creation. It is not known which party submitted the registration. The copyrights list Willingham as author of the text, and DC as author of the art via work for hire.

The partnership between Willingham and DC did not live happily ever after, as disputes eventually arose. These disputes included DC failing to consult with Willingham when contractually required, underreporting his royalties, and trying to convince him to write future issues as “work for hire.” These slights culminated on September 15, 2023, when Willingham announced on his Substack that “the comic book property called Fables, including all related Fables spin-offs and characters, is now in the public domain.” His subsequent posts reiterated this point, saying, “As the sole owner and creator of the comic book property called Fables . . . I alone had the right . . . to do this.” He posted four blog posts in total discussing his decision. Willingham chose not to publish his full contract with DC for privacy reasons.

DC responded to Willingham’s declaration with its own, saying “The Fables comic books and graphic novels published by DC . . . are owned by DC . . . and are not in the public domain.”

What is the Public Domain?

The public domain is a term for intellectual property that is owned by everyone. Under copyright law, owners hold many exclusive rights to their work, such as the right to publish, reproduce, or create derivative works. By contrast, public domain works, because they belong to everyone, have no limitations on their use.

Some public domain works were once copyrighted, their rights having expired, e.g. Pinnochio or Sherlock Holmes; others were always in the public domain, works such as Cinderella or Snow White that were never granted copyright protection for one reason or another.

Does Willingham own Fables?

If Willingham’s contract says what he claims, he does own Fables. Under copyright law, the author of the work is the initial owner. However, if more than one individual contributes substantial elements to the work, while intending their contributions to join into one joint work, they are joint-authors. Joint-authors each own an equal and undivided share in the entire work. No joint owner can convey more than they own. For instance, none of them can make an exclusive license without the other owners’ written permission since that would violate the other owners’ rights. Comic books where one author writes the text and the other draws the art qualify as joint works. Works made by employees are “works for hire,” where, unless agreed otherwise, the employer is considered the author of the work. Copyrights can also be transferred or assigned.

When a copyright is registered within five years of the work’s creation, the registration and the facts within are presumed valid, which may be rebutted if a party “offers some evidence” to dispute the registration’s validity.

The Copyright Office lists both Willingham and DC as the authors of Fables, Willingham for the text, and DC for the art. Since comic books are joint works, and the copyrights were registered within five years of creation, Willingham and DC comics are presumed joint-owners of Fables.

However, this presumption can be rebutted by showing disputing evidence, such as Willingham’s contract. If Willingham is correct that his contract gives him sole ownership of Fables, then it would prove that DC transferred any ownership it possessed as a joint-author to Willingham. Thus, Willingham would be the sole owner.

It is unknown whether Willingham or DC registered Fables’ copyrights as joint-works. If Willingham did, then DC might try to argue that Willingham did not treat Fables as his. However, such an argument could be countered with the fact that DC themselves assigned their rights to Willingham. Willingham could also point out that he has followed his contract for over twenty years.

How does sole ownership versus joint ownership affect Willingham’s authority to release Fables into the public domain?

Can Willingham Place Fables into the Public Domain?

Willingham has the authority to release Fables into the public domain provided that he is the sole owner. While there is no express provision for abandonment in the Copyright Act, several court cases say that proprietors can abandon a copyright if they both intend to abandon the work and perform an overt act demonstrating that intent. However, an owner must be very clear about what they mean to abandon. Once, a man made several meditation videos and repeatedly said he neither cared about copyrights nor wanted to control his videos. These statements released one of his videos into the public domain, but were insufficient to release his later ones. On the other hand, in 2002 an architect provided designs for a competition, signing a document saying that he retained no copyrights to them. This admission released such designs into the public domain.

Willingham clearly intended to release his work; he said so multiple times. He also made not one, but four overt acts via his Substack posts, which repeatedly stated his intent to surrender all of Fables into the public domain. Therefore, if Willingham is indeed the sole owner, he may release Fables into the public domain.

If Willingham and DC are joint-owners, though, then Willingham cannot release Fables into the public domain. The rule regarding exclusive licenses stipulates that one owner cannot negate another’s right without written permission. Willingham did not have DC’s permission, meaning he cannot unilaterally terminate their share.

What happens next?

DC Comics publicly maintains that it owns Fables, but it has not filed any legal action. Since a lawsuit against Willingham or accused infringers risks a court declaring the entire series to be within the public domain, DC will likely avoid litigation whenever possible. Instead, it will use the undetermined nature of Fables’s ownership to deter would-be copiers through the threat of a potential lawsuit. Things will likely not stand at this stalemate for long though, as there will inevitably be those who take Willingham at his word and use Fables for their own creative works. DC will quickly have to decide how many alleged violations it can let slide before going to court.

Happily Ever After?

If Willingham is indeed the sole owner, per his claimed contract, then a court would likely find the series to be properly released into the public domain. If Willingham is not, then DC retains its exclusive right to publish the series. Ultimately, the answer to this question centers on contract law, specifically whether DC transferred its ownership. Without viewing Willingham’s contract, it is impossible to say for certain who will prevail. Should Willingham prevail, the threat of placing works into the public domain will hand creators a bargaining chip against unscrupulous publishers. Should DC emerge victorious in litigation, publishers will have a reinforced blueprint to compel creator compliance.Will Fables be freed into the public domain to live happily ever after or remain trapped within the walls of its wicked stepmother’s copyright control? We will just have to wait and see.