By: Sarah Fassio

There are 255 human brains in the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum storage facility in Maryland. In Pennsylvania, the Penn Museum housed over 900 human skulls as recently as 2021. The American Museum of Natural History in New York hosts some 12,000 human remains. These collections, amassed throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, represent the non-consensually acquired human remains of historically exploited groups—particularly Indigenous populations and people of color—and are a tangible legacy of white-supremacy pseudoscience in the United States.

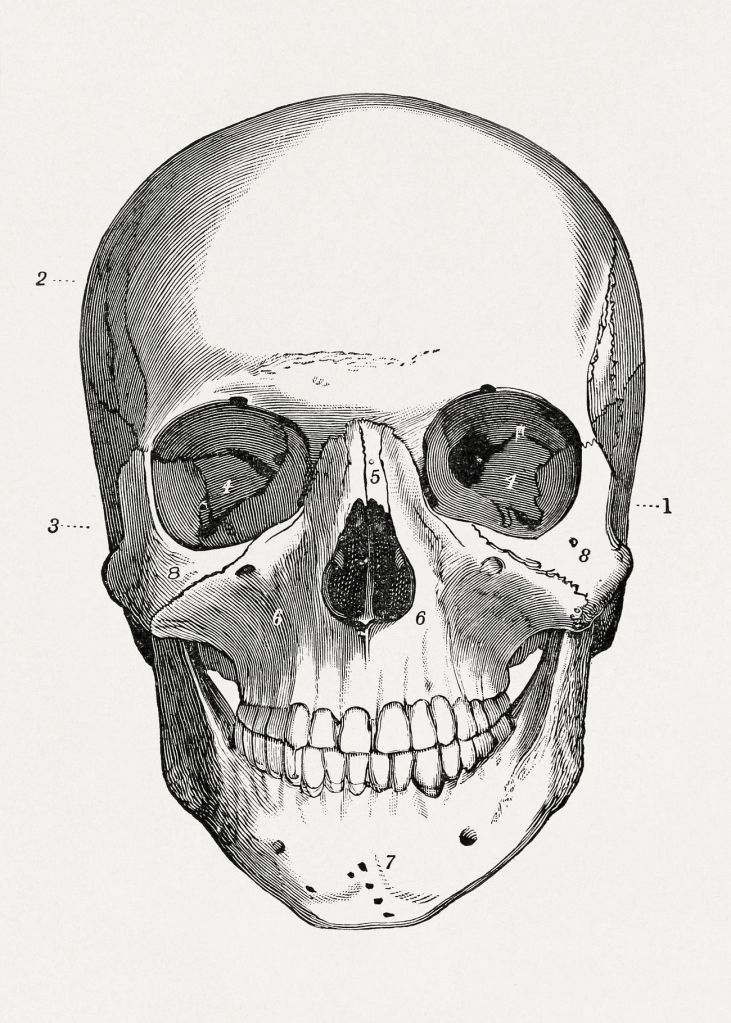

It is an almost cliché tableau: to think of a museum of natural history, anthropology, or medical science is to envision carefully curated exhibits of skeletons, cuts of brains, and jars of preserved organs. Such displays often disquietingly blur the distinction between an impartial, academic teaching tool and the actual body of a real person. They also raise questions about who is being displayed. How did these human remains come to be displayed or acquired by museums and academic institutions?

There are, of course, those who donated their body to science—a practice that is still around today. The University of Washington has the Willed Body Program, a whole-body donation opportunity for individuals from Washington State. Dozens of universities across the country have similar programs. However, whole-body donation in the twenty-first century is a process laden with paperwork and legal boundaries. The Mayo Clinic, for example, requires the prospective donor themselves sign an Anatomical Bequest Consent Form. Signatures from an individual’s medical power of attorney or guardian are insufficient for this process—and if a next of kin opposes the donation, it will not occur.

Historically, such formalized donation schematics did not underpin some of the grander museum collections of human remains nor was their inception so necessarily scientific. Viewed today as discredited pseudoscience, many collections of human remains were predicated on proving the principles of white supremacy and anatomical racism: the belief that white superiority was due to structural differences between races. White scientists robbed graves, exploited those too poor to afford proper burials, or outright stole bodies from Black and Indigenous communities. Many immediate family members were unaware their loved ones’ bodies were held by museums. Many are still unaware.

Faced with such a horrifying past, what can be done to move forward? Are there currently legal structures aimed at encouraging museums to properly confront their human inventories?

The law is not entirely silent on the issue of misplaced human remains. One avenue for recourse for some Indigenous communities is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA). NAGPRA is concerned with items of Indigenous cultural significance, covering things like human remains and funerary or sacred items. It provides a process for federal agencies and museums to repatriate or transfer those pieces back to their rightful homes.

But the more unfortunate truth is that there are not comprehensive laws aimed at ameliorating the ugly collection processes of yesterday’s anatomical racism. The Smithsonian, for instance, requires those with a personal interest or legal right to the remains to submit a formal request. But doing so remains difficult, if not impossible, since many living relatives are unaware these collections even exist—much less that their lineage is an unwilling part of it. The American Museum of Natural History, for instance, holds records naming the individuals to whom the human remains once belonged, but declined as recently as this month to release a list.

Ultimately, change and repatriation seems largely left up to the museum institutions themselves, often motivated by public pressure and activism. The Penn Museum’s recent treatment of the Morton Cranial Collection—900 human skulls obtained by early-nineteenth-century scientist Dr. Samuel Morton for the purpose of articulating racial differences—is one encouraging example of visible change.

Beginning in 2020, the Penn Museum formed an evaluation committee, published a report on contributions to the Morton Collection by Black Philadelphians, and recommended burial and commemorative actions. Among the recommendations were an interfaith memorial service, the erection of a permanent remembrance marker on the University of Pennsylvania’s campus, and participation in a community-led transparency forum.

In February 2023, the Philadelphia Orphans’ Court granted the museum’s request to respectfully bury the cranial remains of twenty individuals in a historic African American cemetery. For those, at last, a final rest.